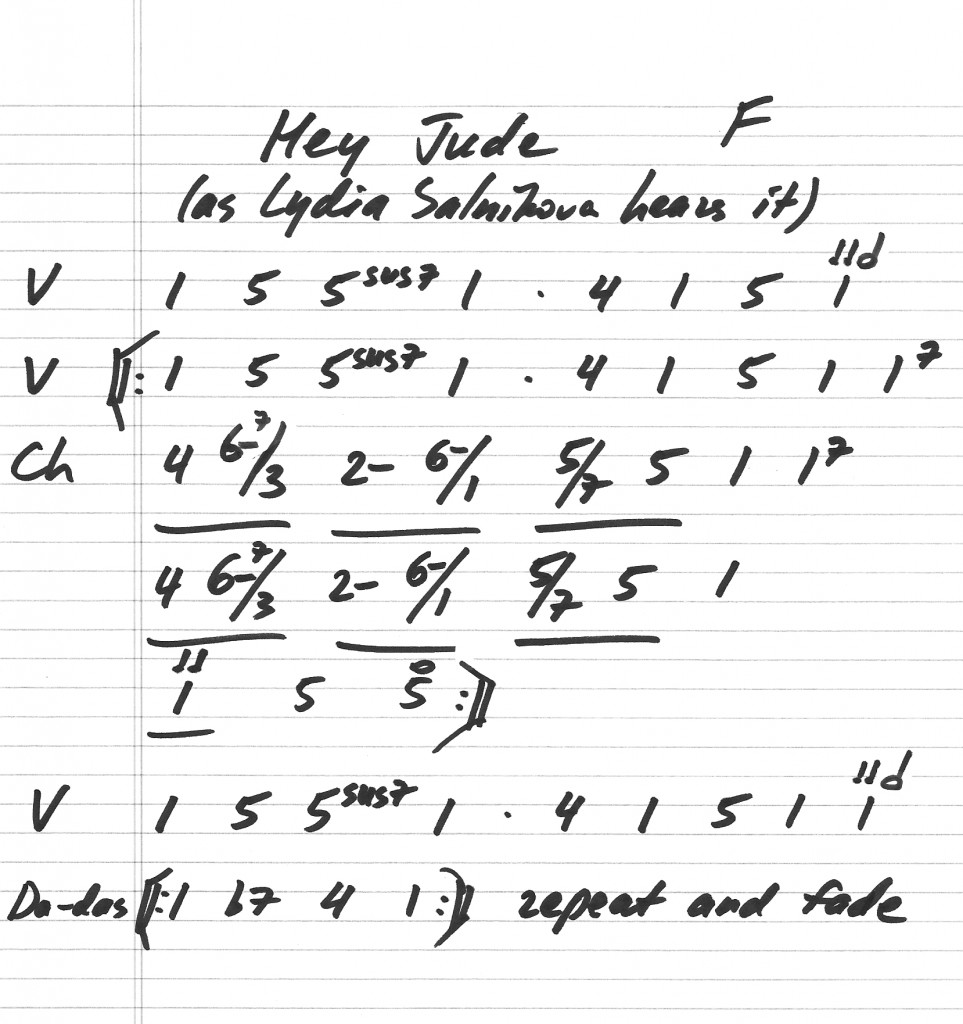

How To Read Nashville Number Charts: Crash Course by Lydia Salnikova

First, a disclaimer… You donʼt HAVE to know how to write number charts. Many professional session musicians (myself included) are willing to work with whatever materials clients give them, or write their own charts. But if you want a bit of “street” music education, a slight broadening of your horizons or simply the satisfaction of being able to speak to musicians in their own language – read on!

The concept is simple enough: instead of letters representing chords, number charts use numbers. In the key of C, “1” is C major chord, “4” is F major chord, “5” is G major chord and so on. In essence, all numbers are relative to the root note of the songʼs key, and therefore the chart does not change if the key changes. A standalone number represents a major chord, for a minor chord a dash “-” is added after the number.

Compound chords (slash chords) are used for chord inversions and chords with altered bass notes. Accidentals (♯, ♭) are usually written to the left of number, although Iʼve seen it both ways. Dominant sevenths, major sevenths, suspended chords and such are indicated with superscript, although Iʼve seen subscript also.

Now, in terms of structure – one number equals one measure (bar). If there is more than one chord in a bar, itʼs a “split bar”. Split bars are either underlined, or enclosed in parentheses, or separated with a forward slash… That last one Iʼm not so fond of, I prefer to leave slashes for compound chords, so I underline my split bars. Split bars are assumed to be evenly divided, unless otherwise indicated with dots, hash marks or rhythmic notation. I prefer the latter.

Naturally, some rudimentary knowledge of music notation is needed here, such as: repeat signs, first/second endings, D.C. and D.S., fermata sign (“birdseye”), pushes (an eighth note with a tie indicates a push, or “<“ and “>” can be used), marcato signs (for chokes/stops, or I sometimes just write “stop” underneath), crescendo/decrescendo symbols, ritardando symbol (rit. or ritard.) and a few others.

For dessert, hereʼs one peculiarity Iʼve noticed about number charts… They are very rarely written in minor keys. In other words, you will almost never see “1-” chords thrown around. “1” is inherently, or 99% of the time, a major chord. So when the song begins, say, in D minor and arrives at the relative F major at some point later, perhaps in the chorus, that first D minor is automatically “6-” and the key of the song is F. And even if the song never gets to the relative major, not even in the chorus, that “1” is still somehow implied and the first chord is still “6-”. Donʼt ask me why, I donʼt quite understand it myself… Iʼm sure thereʼs an official explanation for it somewhere, buried at the bottom of a deep ocean.

If all of this sounds more complicated than regular chord charts, it might be… At first. Once you get the hang of it, it makes life a hell of a lot easier. And that means something, coming from a classically trained pianist (me).

Finally: to illustrate number charts, also known as Nashville number system, I am attaching a number chart I wrote for one song you might be familiar with. For the record, this is how I personally hear the chords in that song, so Sir Paul hasnʼt signed off on them – but for a quick illustration this should suffice. Have fun with number charts, and have fun playing music! Ciao.